Choosing an impactful business structure

Please note: The information in this article is specific to Canadian companies!

When setting up a studio, one of the first – and maybe scariest – decisions you’ll make is choosing the right business structure. This structure will affect your studio’s governance, funding options, and growth potential. Remember that project-based funders rarely care about your studio’s structure or sustainability. We’ve seen them push for hurried incorporation to facilitate their funding. Before you jump to incorporate, consider your studio’s long-term goals, where you might seek funding, and the impact you want to make in the world.

If you’ve already incorporated or worry about needing to before you’ve had the time to think through all of the possibilities and implications, approach this as if you have lots of time and have not made any irreversible decisions yet.

Of course, the requirements of the big government funders in Canada may influence your decision, but it should not be the only input, and we want you to have a complete picture of your options.

Weird Ghosts believes indie studios should establish their companies in alignment with their social purpose – instead of being driven by project funding, aka the “old normal” that leaves no room for new founders to create a solid foundation.

Results flow

A results flow is a roadmap describing the impact you want to make and the activities you’ll need to carry out to achieve it. If you have the chance, draft your results flow before deciding on the form of your studio. It may make your choice a lot easier.

In addition to helping you identify the most appropriate business structure, your results flow also:

- Helps you create your impact measurement framework (IMF), allowing you to monitor progress toward your key outcomes

- Forms the foundation of your business plan and helps you develop and evaluate your business model

So, super handy if you’re preparing to pitch investors or publishers!

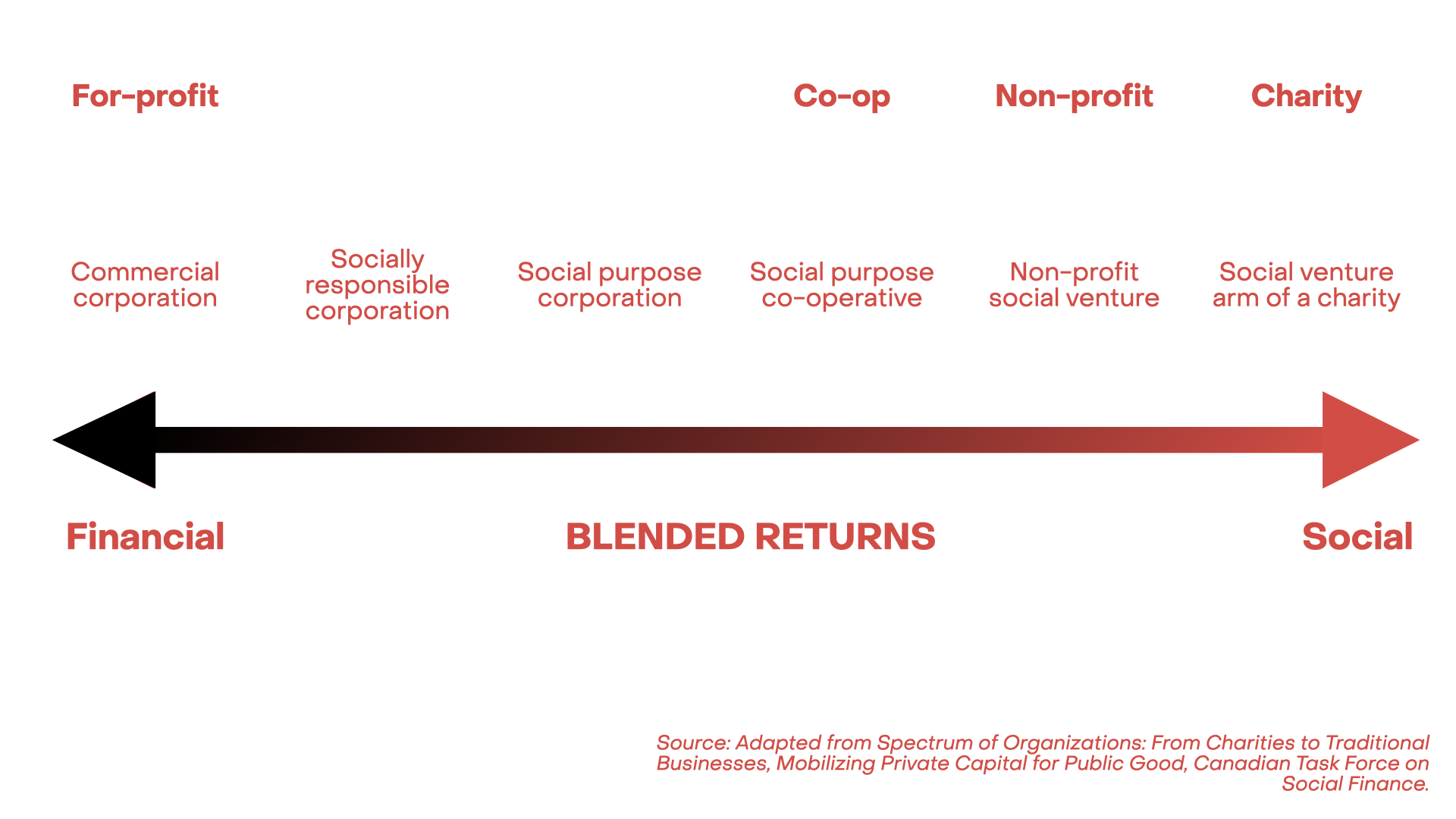

Blended returns

Blended returns combine financial and social returns and are at the heart of Canada’s $755 million Social Finance Fund. You have a few options when selecting a business structure that will provide blended returns and set you up to access social financing:

- For-profit structures like socially responsible corporations

- Co-operative social ventures

- Non-profit organizations and co-ops

- Charities, and social purpose businesses

Whichever path you choose, remember that incorporation will affect your governance structure and your ability to secure investment and other types of funding. It also may preclude you from accessing certain kinds of investment. For example, non-profits cannot offer share capital and will typically need to look to debt financing. And a for-profit that values social return over financial may be a hard sell to traditional investors.

Whether you decide to incorporate as a for-profit company, a non-profit, or a co-op, demonstrating both financial and social returns will be a requirement if you intend to seek social finance investment.

The purpose of a corporation is to generate financial returns. Looking at different types of corporations on a spectrum, you’ll find “pure” commercial operations on one end. The only thing those shareholders and investors care about is making money. They will not care about a social impact report.

Next, we have the socially responsible corporation. It’s hard to find a company in 2023 that doesn’t at least pretend to have a corporate social responsibility policy… because branding and reputation. Lockheed Martin? Even they “give back” to the community by training underprivileged youth so that they may someday, uh, work on hypersonic missiles and fighter jets.

If we keep moving to the right of the diagram, at the end we find that even charities can start a social venture, as long as it aligns with its mandate and strict government regulations.

While demonstrating financial and social returns sounds like a lot – and it is a bigger job than non-social-purpose companies have – the benefit of social finance is that it is structured to be easier for mission-driven organizations to access and manage. So, for example, you will get lower interest rates, more flexible repayment schedules, and possibly zero-interest recoverable grants. Work with investors or funders who fundamentally understand this.

If you can demonstrate solid financial returns, equity investment from a social investor may be possible. But you will have a hard time capturing the interest of a venture capitalist (VC) without the potential for a very high return on investment.

You may be thinking, “We probably won’t be able to generate a financial rate of return at or above market.” Hey, that’s okay! You can focus on investors and partners who will structure a deal with you that isn’t equity-based, like low-interest loans or royalties — or Weird Ghosts’ SEAL agreement

Understanding SPOs

You may be a social purpose organization (SPO) if you are working on advancing social, cultural, or environmental objectives – such as transforming an industry or making an economic impact within a specific community. To access funding from social finance investors, such as Weird Ghosts, you must put impact at the core of your mission and operations.

You’re here because you’re interested in changing what a “normal” video game studio or startup looks like. There’s no set template!

So before getting into the different form options for your SPO, take a minute to think about the following:

Intention and motivations

Which takes precedence – profit-making activities or furthering a social purpose?

While the goals of making money and furthering a social purpose are not mutually exclusive, their relative importance will influence the optimal structure as they will often conflict during your studio’s life.

Knowing what’s most important is critical to choosing a structure that either gives you the flexibility to respond to financial opportunities or ensures your social purpose remains central in decision-making.

Not-for-profit and unincorporated social ventures cannot seek equity financing and may experience other barriers once the venture grows.

Control

Are you open to sharing control? Can you operate and fund the studio independently?

Members in a co-op and investors split control – and priorities may conflict.

For-profit companies are responsible to shareholders, which can cause pressure to favour financial returns. Because there is no legal way to enforce a social purpose within a for-profit corporation, maintaining a focus on social benefit depends on successive leadership sharing the goals of the original founders.

In a co-op, founding member(s) do not maintain control. Co-ops are legally required to operate on a co-operative basis so they can talk about their community-benefit purpose, but maintaining member participation over time can make management more challenging.

Non-profits won’t have investors with conflicting priorities because they do not issue share capital. Social finance investors offer affordable repayable capital and expect social return on investment (ROI) — and to be repaid.

Market

What is the profit potential based on the services and products you intend to provide? Who will be your primary customers – funders or end-users?

If you focus on providing services such as design and development, your profit potential is different from a product-focused studio.

If you expect it to be relatively easy to be profitable, incorporating as a for-profit makes more sense regardless of how your money is spent. If, by contrast, you expect the venture to be challenging to sustain without donations and grants, then a non-profit structure may be more appropriate.

Non-profits are subject to restrictions on the types of business activities they may carry out. The CRA does not want a non-profit to compete with products and services provided by for-profit organizations.

Capital

Will you seek investors expecting a financial return? Can you rely on debt financing? Do you plan to reinvest profits or donate them?

The funds needed at start-up may influence the structure of the venture.

Greater needs for capital and financing flexibility — and in particular, the need to be able to issue share capital — will suggest a for-profit structure.

Non-profit organizations and charities cannot generally access share capital and must rely on debt financing. If you do not hold assets you can borrow against, it may be hard to obtain commercial loans. (Upside is tax exemptions, but this is not super useful if you do not hold assets or wish to present your studio as non-profit.)

Co-ops must operate as close to a cost-recovery basis as possible. Co-ops are generally designed on the assumption that the majority of the organization’s capital will come from the members. However, co-ops are permitted to issue shares and loans to non-members, with the promise of at least a limited financial return on investment. This aids in attracting capital from outside the membership structure if necessary.

Hybrid

Weirdly enough, “social ventures” and “social enterprises” are not real things! Sort of…

Despite the Social Finance Fund launching in May 2023, plus a couple decades of social enterprise scholarship and practices, “social enterprise” is not a legal structure in Canada. In fact, current federal and provincial legislation doesn’t offer any legal structure combining the perks of both the for-profit and non-profit corporations.

But we have lots of options and flexibility when it comes to defining how our companies operate, get financing, and grow sustainably, ethically, and in line with our communities’ needs.

And hybrid entities do exist:

- In B.C., you have the Community Contribution Company (CCC or C3) and Benefit Company (PDF).

- In N.S., you have the Community Interest Company.

- And across the country, B Corporation certification is also an option.

These hybrid structures come with additional reporting obligations and may require amendments to your articles of incorporation. Restrictions on the use of capital can also hamper your funding and financing options.

Co-op

Co-operatives, or co-ops, are a unique business model distinct from business corporations. They were originally intended as a way for people to share resources and are designed to promote equity, create a healthy work environment, and support collaboration.

”A co-operative is a legally incorporated corporation that is owned by an association of persons seeking to satisfy common needs such as access to products or services, sale of their products or services, or employment.” – Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada

They can be for-profit or non-profit, and their goal is to minimize business costs to allow more people to participate. You can incorporate your co-operative either federally or provincially/territorially – but there are some geographical differences in regulations (especially in Quebec).

Even if a co-op is non-profit, it can still charge for its products and services. However, any profits made must be reinvested into the business.

Four broad categories differentiate co-ops from share (business) corporations: ownership, directors, voting, and profit.

Ownership

- In a co-op, shares cannot change in value. When members join, they buy shares at par value, which doesn’t change even if the business is wildly successful (or fails).

- Membership shares can’t be transferred as freely as in a business corporation. A co-op share cannot be sold to anyone else and can only be bought back by the co-op at the same value the member originally bought the share at.

- Ownership is independent of value. The amount of ownership is determined by the number of membership shares held.

- Members sell their shares back when exiting. If a member wants to exit a co-op, their share must be repurchased at the same value the member initially bought it at. If the co-op doesn’t have enough money, they can enter into an agreement where the co-op pays you out over time.

(In contrast, a business corporation is owned by shareholders who invest money and receive shares in return. These shares can increase or decrease in value depending on the business’s financial health. Shareholders have voting power proportional to the number of shares they hold.)

Directors

The number of directors required varies across Canada, typically three. Directors are responsible for the day-to-day governance of the co-op and must always act in its best interests.

Voting

In a co-op, the core value is “one member, one vote,” no matter how many shares are held. This contrasts with a business corporation, where the number of votes can increase with the number of shares held.

In a federal worker co-op, each member has to be an employee. There’s also a rule that 75% of the membership must be employees, but the other 25% can be investment-type shares issued by the co-op.

Profit

When a co-op makes a profit and distributes it to its members, it’s called a “patronage return” — similar to a dividend. Someone who has five membership shares will be entitled to more surplus than someone with one membership share. But again, holding more membership shares does not increase your number of votes.

A surplus remains after all costs, including operating and general reserve (and bonuses or patronage returns if you choose), have been covered.

While co-ops can accept investments, they’re traditionally not profit-oriented entities. This lack of a profit-driven structure and limited shares can restrict growth and deter some investors. Be sure you’re okay with that.

That being said… we believe co-ops are the worker-centric structure of choice, and we’re proud to have invested in Montreal-based worker co-op Lucid Tales. And our first Baby Ghosts grantee was Winnipeg-based co-op Something We Love!

Questions to ponder

When thinking about forming a co-op, consider the following:

- How will you handle surpluses at the end of the year?

- How will you manage the governance of your co-op?

- What happens when someone wants to exit the co-op?

- How will you handle disputes?

A thorough guide to federally incorporating a co-op, and contact information for provincial associations can be found on the ISED site. If you‘re in Quebec, you can find more information at Ministère de l’Économie, de l’Innovation et de l’Énergie or get help from le Réseau Co-op.

Non-profit

Non-profits and charities can be structured in a few different ways. The most common is to be a corporation without share capital. They have no shares or shareholders but members who vote for directors. Members don’t get dividends and (usually) don’t get any of the corporation’s assets if it dissolves.

These types of corporations must have a social purpose. All of their activities must support this purpose.

There are laws about how charities and non-profit organizations can earn money:

- Canada’s Income Tax Act says these organizations can only do certain activities to make money if they want to stay tax-exempt.

- If a charity carries on a business that doesn’t relate to its purpose (unless run mainly by volunteers), it can face penalties, including losing charity status.

- If a charity or non-profit wants to make money to support its mission, it may have to use a separate business corporation to do the activities. Learn more.

Sole proprietorships & partnerships

A sole proprietorship is an unincorporated business owned by a single individual. The business and the operator are the same.

It’s the simplest (and therefore most popular) structure, with minimal or no setup requirements. Your business losses can be deducted from your other sources of personal income. However, this structure only works for a solo dev. You’ll face unlimited personal liability and challenges raising money. Bootstrapping (using your own money) or loans are possible sources of startup funding.

A partnership is the same as a sole proprietorship, except it’s between two or more people. General partners also risk unlimited personal liability, and you’ll have difficulty finding appropriate financing.

Business corporation

A business corporation is a standalone legal entity with rights and responsibilities (just like individuals). They can own property and enter into contracts. They are owned by shareholders and operated by directors and officers.

Shareholders are not responsible for a corporation’s debts. They benefit from lower corporate tax rates and can raise capital more easily than partnerships or sole proprietorships. Unfortunately, business corporations are more expensive to form and operate because of stringent regulatory requirements.

A business corporation’s structure includes the following:

- Shareholders: Own at least one share of a corporation’s stock. Collectively, they own the corporation and get to vote on key business decisions. There can be different classes of shares and shareholders.

- Directors: Elected by shareholders and are responsible for operating and managing the business.

- Officers: Act on behalf of the directors to operate and manage the business. They must be registered and are almost always employees of the corporation.

A major limitation of a business corporation is that there is no real way to build social purpose into the governing documents. Successive directors may change or eliminate the social purpose your founders established.

None of these is quite right…

If none of the existing legal structures perfectly fits your needs, you could use ancillary agreements, policies, and covenants. Your values, ethics, and core principles are also a governance layer on top of your business structure. You can combine different structures and governance models to create a business that aligns with your ultimate outcome.

Some questions to ask yourself if you go this route:

- Is your governance model easy to understand and accessible for diverse stakeholders?

- How do you make decisions?

- Who has a right to participate or vote?

- Who represents whom?

- How can you solve conflicts?

- How do you communicate your governance? Who needs to know?

Some inspirational alternatives

- Distributed co-operative (DisCo)

- Platform co-operative

- Community-centered business, where stakeholders who don’t own shares directly can participate in governance, such as through a stockholding trust designed to represent their interests. More info (PDF).

- For-profit corporation with co-operative decision-making policies… wait, what?!

A co-operative corporation?

Suppose you decide to form a business corporation but wish you had the benefits of collective decision-making. In that case, you can structure it so that everyone is an equal owner with an equal say in the company – nothing prevents a corporation from having employee shares. This flexibility allows a corporation to operate similarly to a co-op without being legally bound to a co-op’s structure. Some examples of corporate-co-op studios include Future Club1 and KO-OP2 (in the process, as of 2023, of converting to a Quebec co-op).

In your shareholders’ agreement, you can include language that prioritizes collectivity, outlines dispute resolution procedures, and details processes for managing a voting deadlock.

You could also consider encouraging your employees to form a union! 👀

Healthy studio culture can be promoted in any organization.

Tip: Establish a founders’ agreement before your company is officially formed. That way, you have processes in place for dispute resolution at every stage of your studio’s development.

Exit strategies

For traditional startups, the exit is everything! It’s the key outcome founders seek. But that’s not you. 😉

It might seem weird and pessimistic to plan for the end of your studio. But it is part of how you can take responsibility for the lifecycle of your studio. Who benefits when your studio is bought by Streamberry? Who ends up with your IP and community infrastructure?

Here are some situations where you might face an exit:

- Someone might want to take over the enterprise (maybe even a co-founder).

- You might be so successful you want to sell off the business and start something new.

- You might want to retire! haha

- If the app you make or service you provide becomes something your community depends on, you might want to transfer ownership to your community. One option is an “exit to community,” an intentional plan where ownership is transferred to a community that manages and benefits from it. This means the studio stays in the hands of those who built it.

Investors will want to know how you think about your exit strategy. Especially if your financial returns are not high, they will work with you to structure a deal that considers this. Please put it in your business plan.

A final note

Our best advice? Go get legal advice! We love and recommend Alex Chun at Dickinson Wright in Ontario. If you need a referral for another province/territory, please get in touch, and we’ll do our best to source one through our networks!