Decisions, Conflict, and Prioritization

Overview

In this exploration of decision-making within a collective studio environment, we navigate the intricate dynamics of collective consensus and collaborative governance. This article delves into the methodologies and practices that make decision-making in a co-op structure both unique and effective. We will explore how to balance individual voices with collective goals, the importance of transparent communication, and the tools and techniques that facilitate democratic decision-making.

What Are Decisions?

So, decision-making! Decisions, decisions, decisions. What exactly are decisions? And why do we decide?

We make decisions to come to a resolution or agreement as a result of consideration. Sometimes, it can be straightforward and swift, and sometimes, it can be really frustrating or even vague and nebulous. So, what do we do? We try to figure out the alternatives and options. We try to gather the information or knowledge that we need to make informed decisions.

When situations, opportunities, blocks, or barriers arise, decisions are important because we need to make a judgment. That judgment will help us to act with as much information and consideration as possible. Sometimes, it’s a worst-case scenario, but sometimes, it’s a breakthrough scenario, where decisions help us to resolve or settle a question or a contest. Sometimes, when something comes up, people have wildly divergent opinions, assessments, or analyses of what’s going on. The decisions will help break a block, stalemate, or place where we feel at odds with what is happening.

It’s worth breaking it out like this because decisions are so present in our everyday – from the time we get up in the morning, to the food we eat, to whether we go to work or not. Do I want to go back to this horrible job? Or do I want to be broke? There are big decisions and small ones – thousands that we all make each day.

There are some truisms about decisions. Because there are a lot of very learned people and people who have gone deep into what it means to make decisions and how they run our lives, and just how all-encompassing our decisions are.

Many people have experienced writer’s block or creative block and have procrastinated. People who have a brain difference or have lived through periods of trauma may find decision-making challenging. When faced with these situations, it can be painful, and sometimes it feels impossible to make a decision. We start to realize that we are our decisions.

Context

Many Indigenous cultures around the world believe that the decisions we make today will affect our descendants for seven generations. This concept applies to things like the environment and how we use our resources. Every decision we make defines who we are, and we often don’t realize it.

Nelson Mandela said, “May your choices reflect your hopes, not your fears.” There are a lot of fear-based decisions that dominate the world and lead to more fear-based decisions that lead to violence, conflict, war, and a lot of harm. It’s worth keeping as a guiding light the idea of making hope-based decisions.

Finally, Roy Disney, Walt Disney’s younger brother, said, “Decision making is easy when your values are clear.” Even at this kind of corporate mainstream level, it’s possible to constantly foreground values.

Approaches to Decision-Making

Majority Voting

In parliamentary democracies like Canada and confederacies like the United States, majority voting is usually the norm. However, what many people don’t know is that there are two types of voting – passive and active. While the former is more common, the latter is more transparent and can be very helpful in documenting one’s consistency and track record of voting, especially in community organizations.

While majority voting requires at least 50% plus one vote, there’s also the concept of a two-thirds majority vote, which indicates a much higher level of support. This is common in places like share corporations and can be essential for ensuring transparency, which is a value that many people prioritize.

Types of Majority Voting

| Type | Voting |

|---|---|

| majority | 50% +1 |

| two-thirds majority | 66% |

| passive | only counted if close |

| active | all votes named and documented |

Consensus/Unanimous Voting

Aside from majority voting and two-thirds majority voting, there is also consensus voting, which involves reaching an agreement through discussion and compromise. This approach can be helpful in situations where there are multiple stakeholders with different perspectives and interests.

Please note that a unanimous vote may not necessarily be the most powerful indication of agreement. Consensus is more meaningful as it shows the level of intention and engagement of everyone involved in the decision-making process. When everyone is in agreement and actively participates in the conversation, it is a clear demonstration of consensus.

Passive Consensus

In contrast, there are instances where decisions are made passively, without anyone actively opposing them. For example, in meetings, a topic may be discussed, and without anyone raising any objections or wanting to discuss it further, the group moves on to the next topic. This is also a form of consensus, but one that happens due to a lack of opposition.

It’s essential to recognize these moments of passive agreement and understand that they are also decisions being made. You might feel uncomfortable or unhappy about the outcome of such passive agreements. It’s crucial to voice your opinion and ensure that everyone is actively participating in the decision-making process.

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Consensus | all present are in agreement |

| Passive consensus | all are assumed to agree unless stated otherwise |

| Active consensus | each person states and documents their agreement |

In a cooperative setting, transparency is essential. Consensus is a great way to achieve transparency, and it is worth considering in the early stages of building a co-op structure, relationships within the co-op, values and alignment.

Where do we make these decisions? And what scope do they have? Structural decisions, such as those that relate to bylaws and legal registration, need to be formalized and made by the whole co-op. However, operational decisions need to be made regularly and collectively. It is important to determine who makes these decisions and how they will be communicated to the group. Is decision-making in the hands of certain people? Is it in the hands of those individuals and not shared between other members? Or are these process decisions being made on a regular basis, and then everyone goes and executes according to collective decisions? It’s a question.

Decisions make collaborations work or not work. Decisions can be made based on information and reflection. And they can also be made transparent by narrating them, documenting them and having them made in advance through conversation and dialogue.

Finally, decisions are made not just at the beginning of the flow but all the way through all the stages of your work. They are going to affect your output, whatever it is – e.g., we chose to hire somebody, we are bringing more members in, we have applied for grants, we are seeking funding, we are developing a game, and we’ve now launched and finished the game. Everything that we have as an output is affected.

Let’s recap the typical location and scope of decisions:

Members are responsible for decisions that affect the co-op as a whole, so they are co-op-affecting. (If this is not done by members, we’re doing something wrong!) Directors are process-affecting. They might hire based on the decisions of the members (this can be written into the bylaws in very specific ways). Management is collaboration-affecting, e.g., how you run a meeting. Workers make decisions around output-affecting things.

Node-Based Decision-Making

Gamma Space has a complex node structure that can be confusing to navigate. Let’s take a closer look at the flattened node view we discussed earlier. It’s a series of expanding circles with nodes attached to them. Although members are still responsible for making cooperative decisions, those decisions are passed up through the node structure to the directors, who help inform the decision-making process.

When we enter a node, we can see that it’s responsible for three things: coordinating the process, facilitating collaboration, and delivering the final output. These three responsibilities are always in service to what the members have said they want to achieve. Inside the node, there is a lead member, a support role, and ad hoc participation by other members or contractors. This structure is decided at the node level and passed through to the rest of the team.

If we dig deeper, our community functions are essential to how the cooperative operates, and members participate in these functions based on their respective responsibilities. For example, if we have a governance working group, the directors don’t make decisions on collaboration independently. Instead, they collaborate with the group members to make decisions based on a menu of processes available in our operations manual or develop something new. Members still play a significant role in the process.

So, when we talk about the collaboration method, it’s still the members who contribute to the output. Each member has a self-contained node, and these nodes have microcosms of all the essential functions. We keep iterating through these different layers and circulating them around, trying to come up with different orders that make sense. We document our progress as we go along.

Values-Based Decision-Making

We have now explored the concept of decision-making, its scope, and its areas. But what about decision-making based on values? When our values are evident, decision-making becomes easy. Understanding the reasons behind it can be helpful.

Values provide direction, motivation, and grounding. When we articulate who we are as a studio, why we collaborate, and what we aim to create, making decisions in all directions becomes more comfortable. Even on groggy Monday mornings, when we wake up feeling overwhelmed by the stresses of the week before, our values help us navigate the day better. When our values are clear, we know what to expect, and we can face the day with a sense of purpose.

Values also help us clarify who is going to be impacted by decision-making? Who needs to be included in any given set of decision-making? And who are we seeking to empower through those decisions?

There’s an expression that came out of disabled people’s organizing in South Africa: “Nothing about us, without us, is for us.” This expression has been applied in many different ways since it came forward in the 1980s. Who is going to actually make the decisions? How are we going to empower those people? Think about how your values inform that.

What is values-based decision-making? What values? Values help determine the needs that we have for our studio and for our individual members making games. They help us with the Layers of Effect exercise, which we will come back to later. What do our decisions determine in terms of our needs, goals, activities, and the resourcing and capacity that we have?

How do we do it? It’s a process that will help us define:

- WHY: provides direction, motivation, and grounding

- WHO: clarifies who is impacted, included, and empowered

- WHAT: determines needs, goals, activities, resources, and capacity

- HOW: describes the process to inform, discuss, choose, prioritize, distribute responsibilities, document, execute, and measure our work

For the people who make the decisions, that’s a lot of responsibility and accountability. And it’s a lot of power in the micro and in the macro.

Document decisions. Documents serve as a guide and a reference point for how we execute our work. When we establish a structured decision-making process and consistently practice it, we can anticipate and measure the impact of our work. We can make better decisions and have a clear understanding of our work before we execute it.

Applying our values helps us to prioritize our needs based on what matters most to us. By doing so, we gain a better understanding of the environment we’re working in, including the resources we have available, such as people, talent, time, and cash flow.

Our values also determine how we schedule our priorities and allocate responsibilities among team members. Depending on their experience, skills and training, some members may bear more responsibility than others for certain decisions. This helps us to determine the level of commitment and intensity required for each activity.

Lastly, our values guide us in making and documenting our decisions, ensuring that they align with our principles and beliefs.

Tool Examples

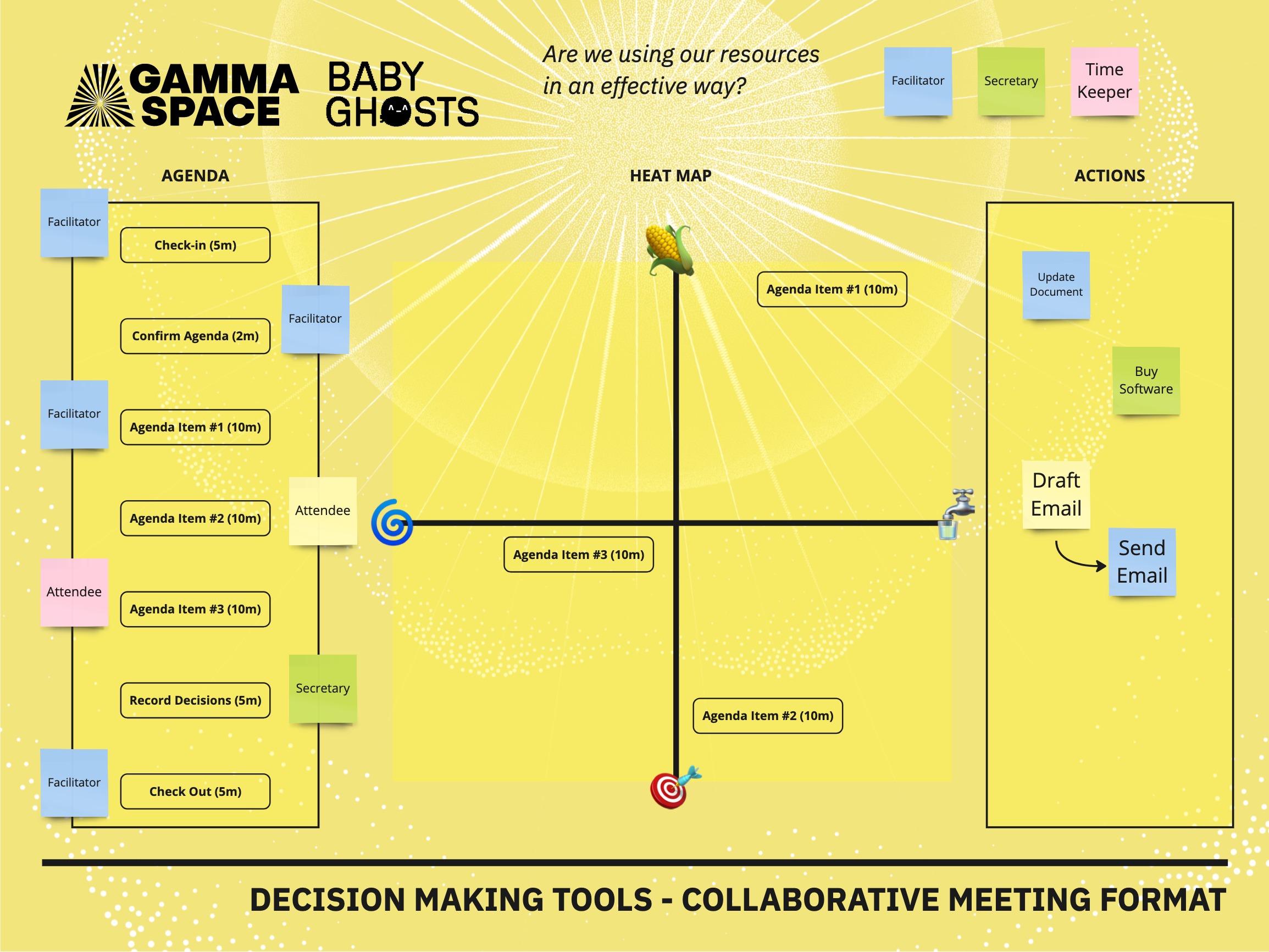

Collaborative Meeting Format

Gamma Space has developed a set of tools that align with our values and meet our needs. These tools are centred around the concept of meetings and how to conduct them effectively. It involves understanding our resources and power dynamics and creating meeting formats that can be adapted for various situations. The ability to have different people lead and take on different roles in these meetings is a powerful tool.

It’s important to think about the outcomes of these meetings and learn from the process. By using visual collaboration methods, this learning process can be sped up.

One of the first things to think about is roles. If one person is always the facilitator, they may be seen as a de facto spokesperson or leader. This is why we rotate that role between members, giving everyone the opportunity to learn new skills. It’s important to try to rotate in folks who find it uncomfortable – not to punish them, but to align your practices with your structure and values. (Of course, make space for illness, anxiety, and other accessibility considerations and don’t force a role on someone who really doesn’t want to do it.)

Give everyone an equal opportunity to contribute when starting out. This covers various responsibilities, such as collecting agenda items if you’re the facilitator and ensuring that there is a designated speaker and a rough estimate of how long they will speak. This creates an opportunity for the timekeeper to guarantee a smooth flow of proceedings and ensure that we stay within time at various stages of the meeting. Lastly, there is the secretary role, which involves writing minutes and sometimes creating visual aids.

These will vary by the type of meeting and how you decide to record things. But it’s important to designate someone to document or be responsible for the final outputs of a meeting.

First, the agenda. We often make agenda items as visual objects that can be moved and dragged around our Miro board. We describe:

- the duration of each topic in minutes

- who is bringing that item forward

- value flow by emoji (that is, is it related to livelihood, community, intention, or self?)

Right off the top, we have check-in – usually just a simple question that can be answered in a few words, like, what’s your temperature/weather/vibe today. We then take a moment to confirm the agenda and revise it with any last-minute additions or removals. We make sure that everyone is represented on the Miro board by a different coloured sticky.

Next, each person who is bringing a topic forward identifies the relevant value flow emoji and places it on a Cartesian plane. You can see there is a continuum between different value flow types, such as between self and community; and between livelihood (which is really about resources, either for an individual or for the co-op, depending on the scope of the meeting) and intentional work or something that might be traded in kind.

During the meeting, we move these emojis around the board. Sometimes, we take a snapshot of our value flow map before and after the meeting to see how perspectives changed.

Each of those items can have sticky notes with more details, as well. This way, we can see how the dynamic of the conversation progressed, which then leads us to extract action items.

The secretary carefully records decisions and action items, such as:

- Update a document

- Buy the software we’re talking about

- Draft and send an email

For each action item, we can identify which value flow it relates to.

This is just one example of how decision-making can work. No matter what structure or process you choose, it’s helpful to think about:

- Where are you spending your time in a given meeting type or area of your co-op’s development?

- If you’re spending all your time talking about one topic, is that having a detrimental effect?

- What areas have been neglected in the last few meetings?

- What tools can you use to ensure neglected areas are addressed more frequently?

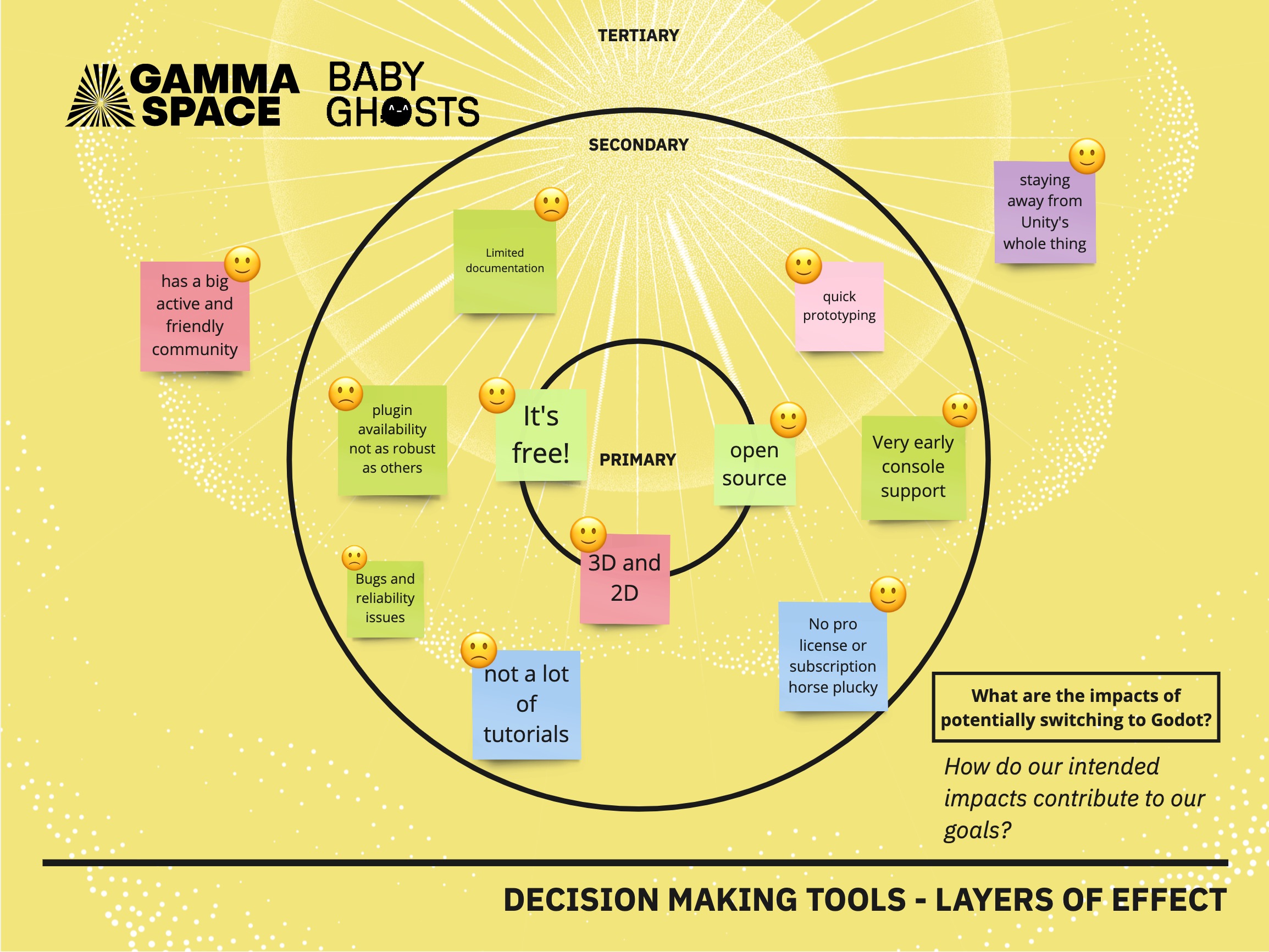

Using Layers of Effect

You might be wondering why we’re bringing back the Layers of Effect. Haven’t we already talked about it? We did, but now you might have more context, and it might make more sense. This tool aids decision-making, helping us understand how our intended impacts contribute to our goals.

We’ve mocked up what it would be like to discuss switching to Godot, for example. Now we can see what that decision would mean for our studio. Is it important for us to prioritize open-source tools? When we make a decision like that, and it’s beneficial, we can measure the impact and make a decision. We can visualize it and decide.

You can mix and match these different tools and components to meet your needs. You will learn what works for you and your team. These are just examples; you might have other ones that work better for you. We always encourage folks to develop their own processes because they’ll be more likely to fit your unique values and represent you as individuals in the studio. All of these tools are hackable! Here’s the Layers of Effect template.

Data-Informed Decision-Making

One way to make decisions that are auditable and data-informed is to use some sort of measurement framework. In our example, we’re using an impact measurement framework (IMF). Developing an IMF is recommended if you are aiming to have a social impact in your studio. You can learn more about this topic here.

One thing we measure is the number of active participants in Slack over time. Assuming we recorded an increase in active participation over a quarter, we would make certain decisions based on that, as increased activity implies greater engagement. It also might tell us about specific topics or times that people are more interested in or active in. Given this interest, we would increase our investment in resources in community-building. We could bring more folks into the community if we see exceptional active engagement. This is one way that we can use data to directly inform decisions in a way that’s responsive to the life of your community or your project.

Values-Informed Tools

When selecting or designing decision-making tools, allow yourself to be guided by the underlying principles of your cooperative. This may seem obvious, but it’s worth repeating. Incorporate your values to ensure equitable outcomes, and make sure they are easily referenced, tracked, and summarized. Even if transparency is not one of your core values, it should be a part of your key processes. You could use a value slot to express that you value transparency, but it might be more helpful to articulate how your studio is trying to achieve transparency in a specific way.

Conflict Resolution

Sometimes, when decisions get made without transparency because people are just rolling with things, conflict can arise. To balance out this topic today, let’s look at conflict and conflict resolution.

Reaching a consensus decision or even a majority decision is a collaborative process that involves coming to an agreement through different means. However, conflict is the opposite of this. It is a serious disagreement that cannot be resolved smoothly through normal means. Conflict can become protracted, frustrating, and debilitating to progress in work. It can also cause hurt, pain, or stress that makes it difficult to go to work. Essentially, conflict arises when a person experiences a clash of opposing wishes or needs.

We have discussed the importance of considering needs in addition to goals and aligning them with factors such as capacity. Conflict may arise when there is an incompatibility between two or more opinions, principles or interests, which can stem from a difference in values. Begin by identifying and articulating values, as this lays the foundation for smooth communication and collaboration. When values are clearly defined, everything else becomes much easier.

Pseudo-Conflict

Conflicts can take various forms. Sometimes, what people perceive to be a conflict is actually a pseudo-conflict or nothing more than a misunderstanding. Misunderstandings can be a result of misalignments in communication. Take the time to assess each situation carefully, giving yourself and others involved some space and time – which can change your perspective. If you can, chat with a friend you trust. You may come to realize that you agree but simply don’t understand what the other person is talking about. Take a step back and try again.

Simple Conflict

An example of a simple conflict is when you say, “Let’s agree to disagree. I don’t agree that making this decision in this way is in our best interests, but you have presented a really good case.” Imagine your team is deciding between using Unity and Godot. If you are not the person working in the engine every day, you might disagree with the switch to Godot but decide to go along with the majority vote because it’s not your role.

Ego Conflict

There are also ego conflicts where things get personal. Someone may say, “I’m the sole expert on this thing. I’ve got all these extra years of experience,” or “I’ve got this award.” Instead of being able to be flexible and open to other opinions and perspectives, no matter where they come from, their ego prevails.

That’s often where conflicts become personalized and framed as character differences. There are many ways in which we perceive that this person can never get along with this other person. That’s why we need to understand what is actually a conflict. If we come back to the touchstone of our values, the type of conflict might be made clear, and how to go about resolving it can be made clear.

Resolution

So that takes us to conflict resolution: a formal structure of policies and processes that everyone agrees to before conflicts arise the pre-agreed policies can help to depersonalize conflict and the steps to resolution can set the stage for a third party to support your process

It’s best if everyone agrees to these principles and practices in advance. Take an average afternoon, order a pizza for the team, or go onto Zoom and discuss conflict resolution while there is no conflict in the mix. Don’t wait for a crisis.

Setting up a formal structure and set of policies can help to depersonalize the process and the steps to a resolution. It drains the intensity and drama out of the conflict. It helps everyone see things more dispassionately, even if at the beginning and the middle, you felt nothing but passion! And it’s also allowing the people involved to say, “This isn’t about who I am. It’s about what’s at play or what’s at stake.”

Conflict resolution also sets the stage for a third party to support your process of resolution if things feel like they’re too twisted, tangled, or personal within your studio. A third party can come and look at the processes that you have and actualize and animate them.

So why do conflict resolution? Like anything – an illness, infection, strained muscle – if you leave it unaddressed, it will get worse. If you avoid conflict by not following a process and giving it time and space (but not too much time and space), the problem can escalate. It can cause a lot of harm – sometimes irrevocable harm or harm that ends up breaking things apart.

Prevention

Prevention of conflict is the best medicine, just like anything that feels painful, hard or difficult. But not all conflict is necessary to avoid, and a lot of times, we grow through conflict! Early intervention in conflict can be beneficial and also vital to fostering deeper collaboration and maintaining a healthy and respectful creative environment.

Sometimes, early intervention is not possible. Sometimes, team members don’t agree that something is a conflict, or they don’t believe it is yet at the intensity or scale that’s worth addressing. And so it festers. How do we do prevention in this situation?

We suggest that you research and understand your individual conflict style in advance. Remember: Conflict resolution isn’t just done at the time of conflict. It is something you should anticipate. It’s part of life. You don’t have to see it as only dire and painful because conflict leads to change and sometimes radical transformation and growth.

Here are some steps to take to start addressing conflict:

- Research and understand your own individual conflict style.

- Collectively create a conflict resolution process that suits your studio, your core values and your culture.

- Decide who will be the contact person or people managing your formal conflict resolution process.

- Establish a third party (or even two) to serve as a backup in case the contact person is involved in the conflict.

- Educate each other regularly about the conflict resolution process and encourage changes to it.

We are a diverse group of individuals gathered in this room today, working together in a coalition despite our many differences. Every person has their own unique journey in life, which leads to differences in opinions and perspectives. However, in our studio work, there tends to be a dominant culture that forms as a result of the relationships we build. That’s why we place a strong emphasis on our values, to ensure that they are aligned and become an integral part of our workplace culture.

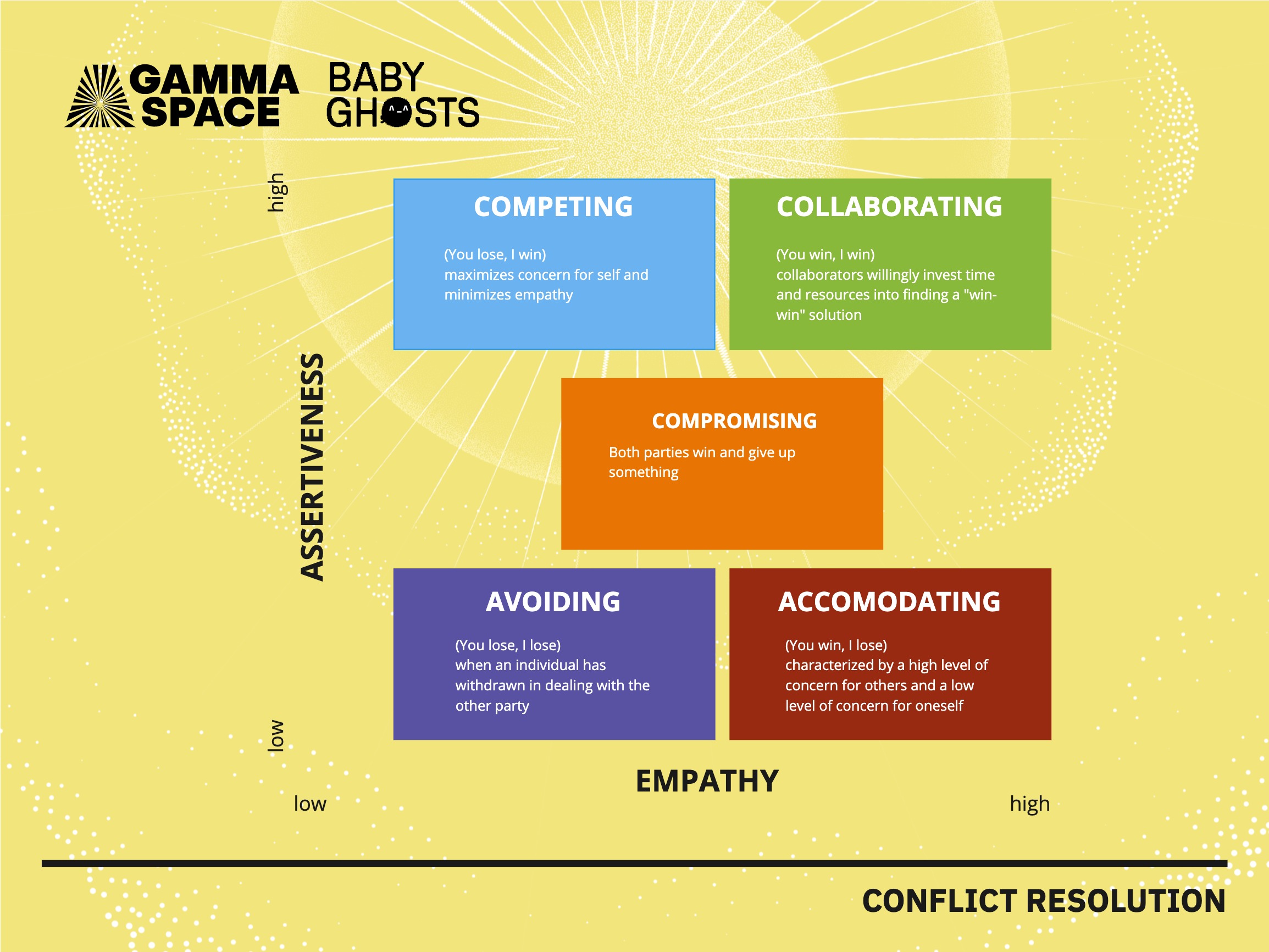

More on Personal Conflict Style

There’s a lot of research that’s been done on conflict because it’s so ingrained at the interpersonal, family, neighbourhood, school and community level.

Take a group project in school as an example. You may remember those leading to conflicts. Someone would end up doing more work than others, or someone wouldn’t do any work at all. But we rarely asked our teammates why. Maybe they were sick, going through hell at home or simply couldn’t understand the assignment. We never knew for sure because we probably avoided those important conversations.

But by examining our own conflict styles, we can start to understand why certain situations may arise. For example, some people may tend to compromise too much when trying to please everyone in the group. Others might avoid conflict altogether, thinking that any disagreement could result in a loss for everyone. Meanwhile, some might be overly accommodating and give in too quickly, leading to feelings of resentment. Then, some compete fiercely due to their competitive nature or upbringing.

Understanding our own conflict styles can help us navigate projects and other situations more effectively. By recognizing our own tendencies and those of others, we can work together toward a more productive and harmonious outcome.

We don’t know where these conflict styles originate, but they can be both beneficial and harmful to our studios. The Thomas Killman model provides a scale to measure these styles in terms of empathy (low to high on the bottom) and assertiveness (low to high on the top), which is worth researching. Understanding your own conflict style and sharing it transparently in meetings can help us learn about each other, increase empathy, encourage assertiveness, and ensure everyone participates fully without being left out.

Conclusion

Putting it all together:

- Values inform decision process and priorities

- Structure informs flow of responsibility

- Goals and impact help measure success

- Understanding conflict happens is the best prevention

Everything comes back to values. Values play a vital role in shaping our decision-making processes and priorities, whether we express them or not. They are always at play, guiding and informing our actions. When we work together in a collaborative and cooperative environment, it is crucial to be transparent with our values, allow them to guide us, and bring us in alignment. This helps us make better decisions, organize responsibilities, and streamline our work. For instance, it can be helpful to have guidelines for note-taking during meetings, creating agendas, and mapping out our plans. It is also essential to be clear about our goals and the impact we want to create. Ultimately, our values drive our aspirations and desires to make a positive impact. Finally, we must acknowledge that conflicts are inevitable, but we can prevent them by understanding their underlying causes.

Questions to Consider

Here are some things you can think about related to structuring and decision-making within your team. As you discuss these ideas with your team, consider how your intended structure affects roles and decision-making. You should also consider how you can evaluate and communicate your conflict resolution style to your team members. Be aware of your own tendencies and share them with your team.

- Do we all have to come together to make creative decisions equally?

- Do roles and structures encourage hierarchy?

- How does individual agency affect decision-making in more minor decisions?

This content was developed by Gamma Space for a 2023 Baby Ghosts cohort presentation. We have summarized and adapted it here.